National Geographic Nostalgia: Alone Across the Outback

On Robyn Davidson’s long walk west

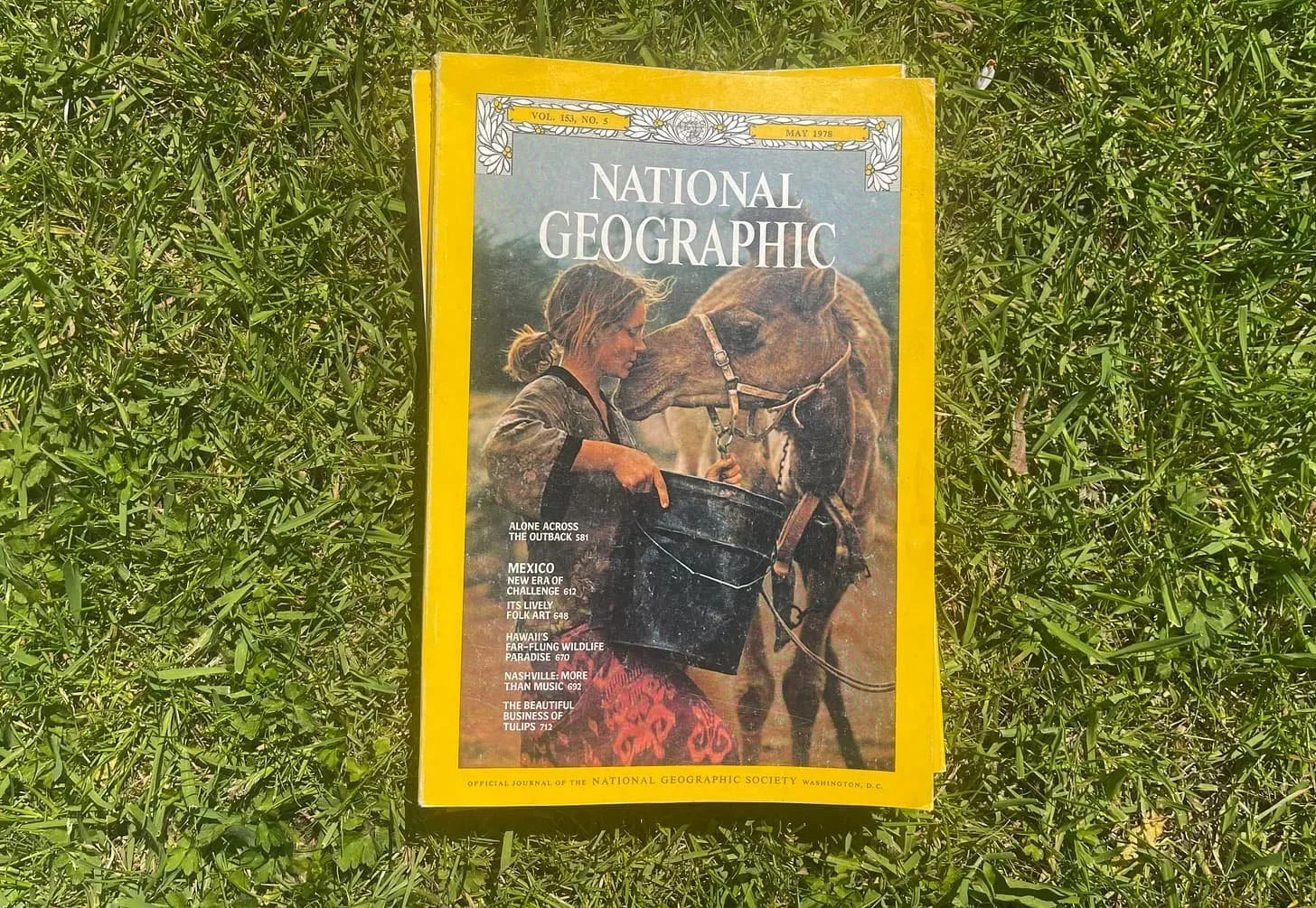

Originally published in National Geographic, May 1978.I’ve been thinking about a National Geographic story that I’ve held onto for years: Robyn Davidson’s 1,700-mile journey by camel across the Australian Outback.

It’s now one of the most mythologised journeys in Australian memory. But the version published in National Geographic in May 1978 feels rawer than Tracks, or the film that came later.

Growing up in rural Shropshire in the 1980s, I had a stack of National Geographic magazines in my bedroom, handed down by family friends and neighbours. I spent hours with them, travelling far beyond my little world. This was the magazine at its peak—twelve million subscribers in the United States alone, and a confidence in long-form photojournalism that trusted the reader’s attention.

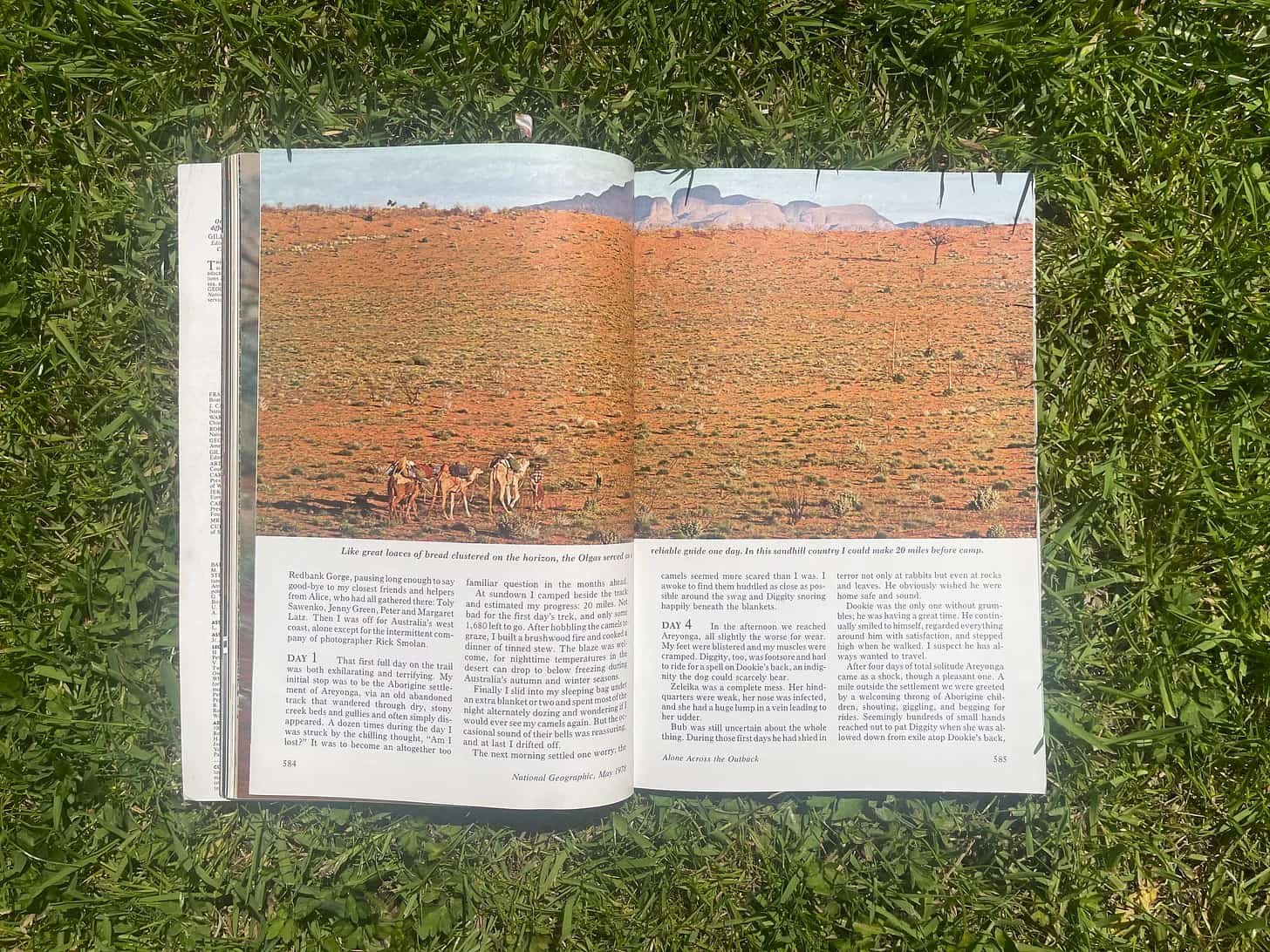

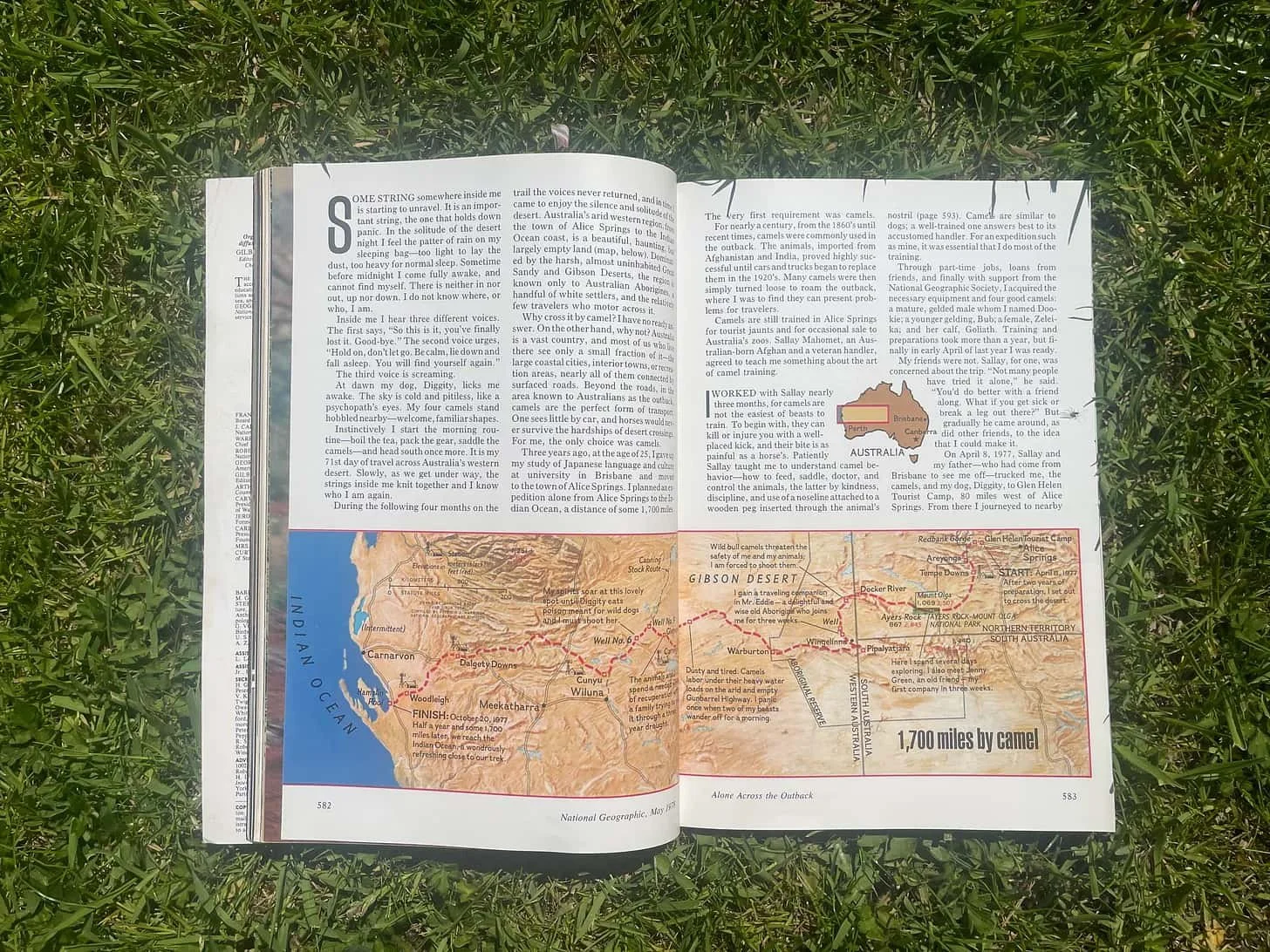

The May 1978 issue follows Davidson’s trek across the Simpson Desert, from Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean. She arrived in Alice Springs in 1975, aged twenty-six, with what she later called a “lunatic idea”: to cross the Outback with four camels and a dog. She intended to go alone. Money was the obstacle.

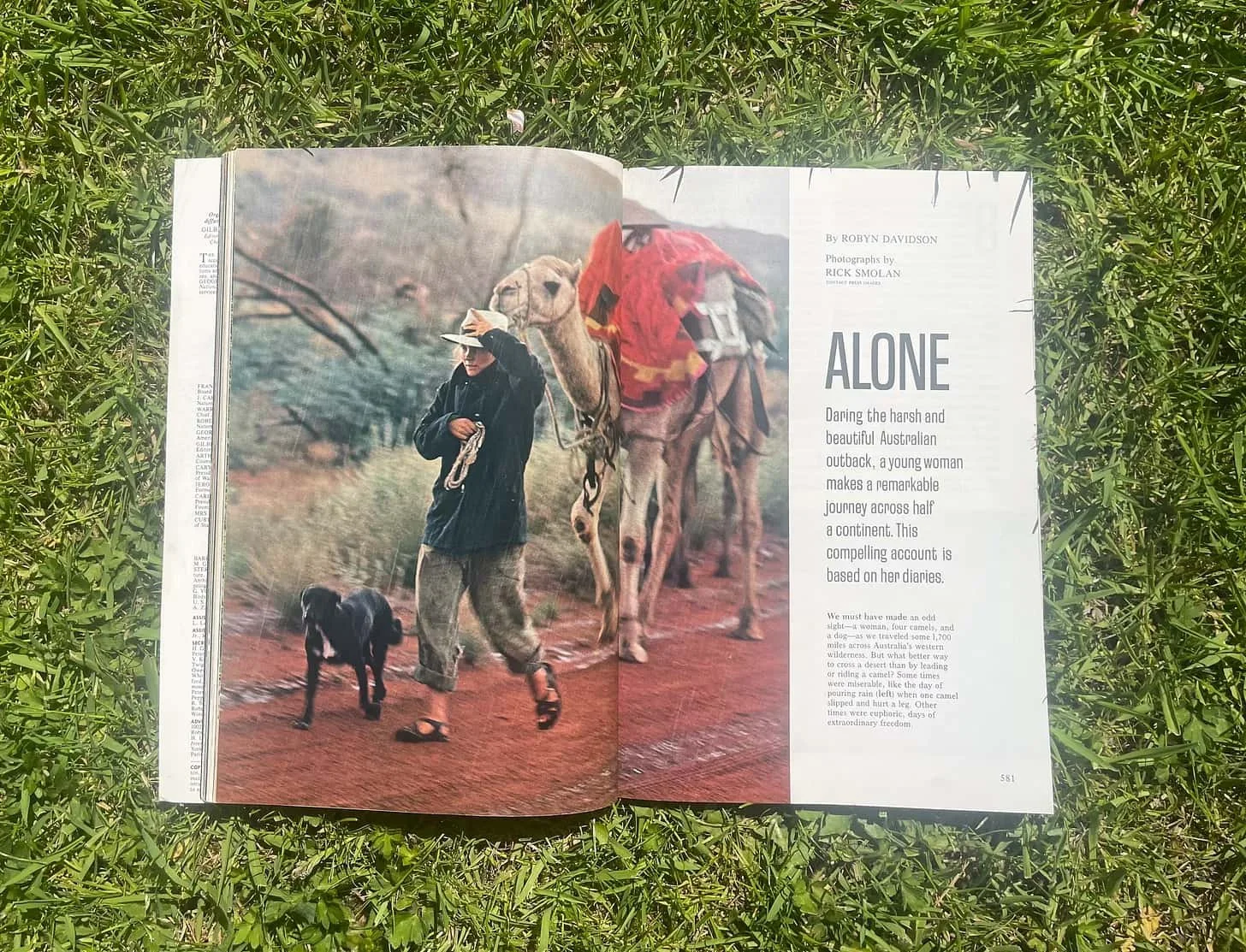

Rick Smolan, then a young photographer, suggested she sell the story to National Geographic to fund the journey. Davidson didn’t want a photographer there at all. Smolan’s presence was a compromise—practical rather than creative—and the tension remains visible in the work. The fee was $4,000. Smolan would meet her intermittently in the desert to photograph the journey.

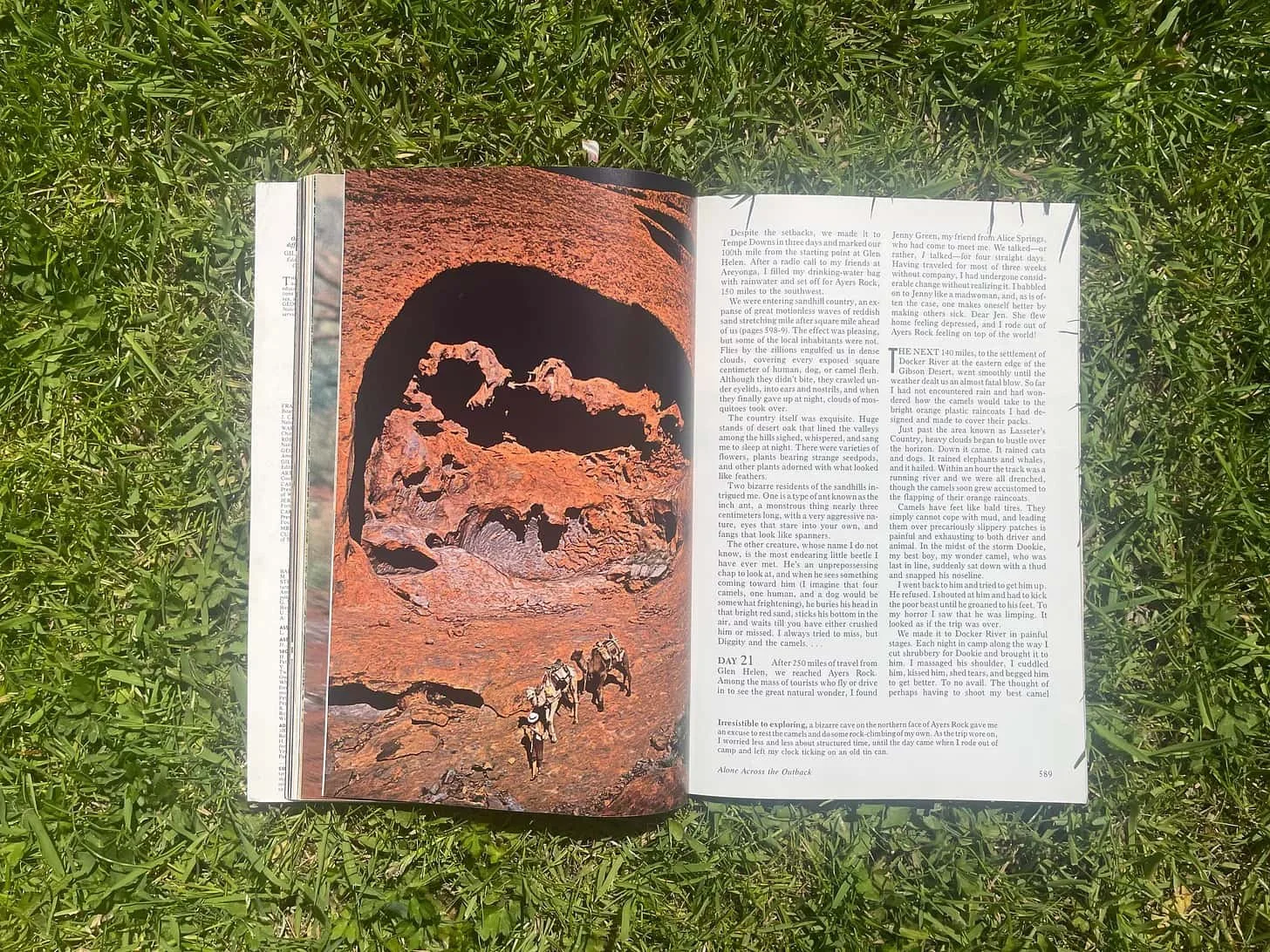

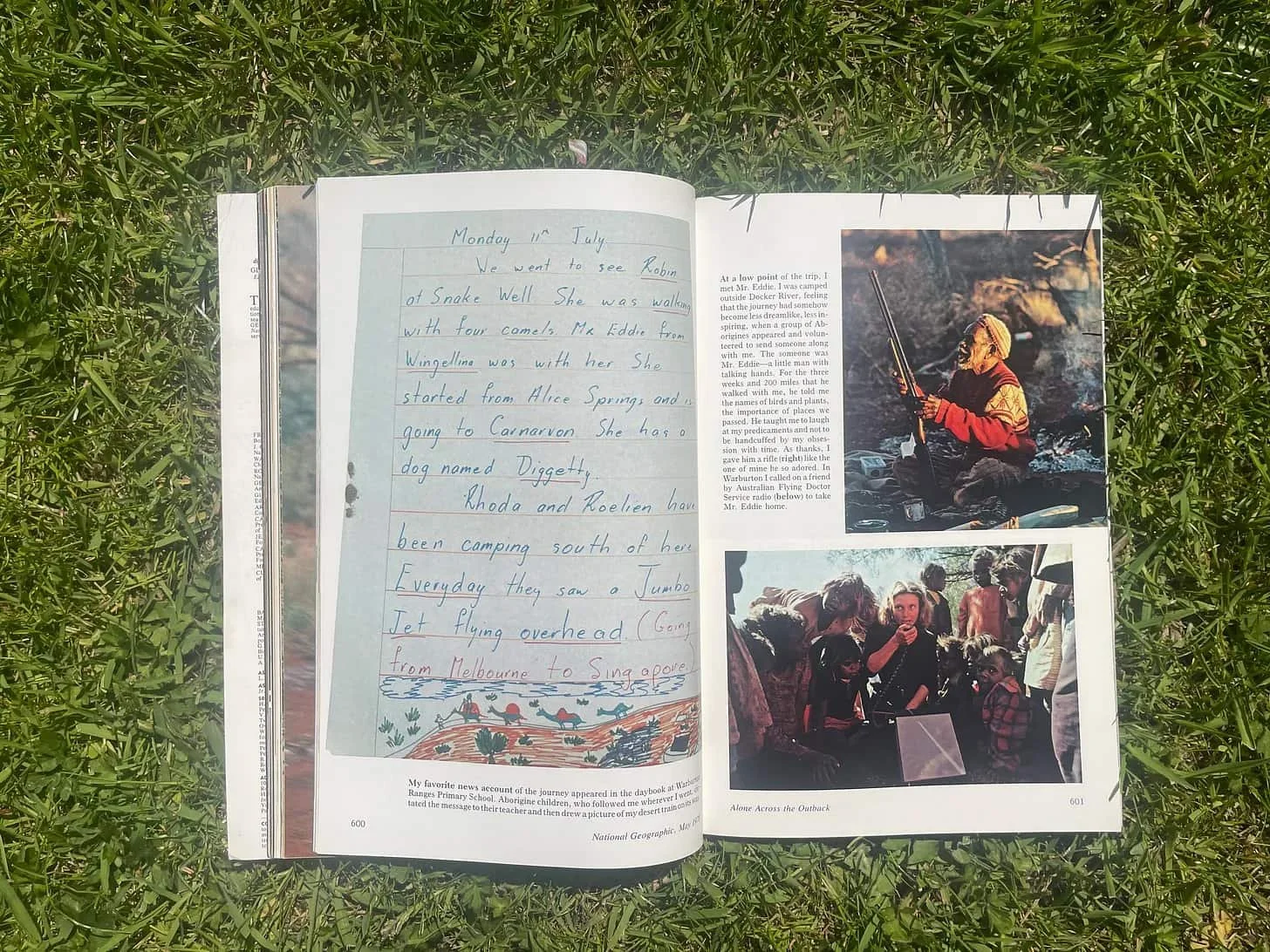

The resulting story is not a comfortable collaboration. Davidson’s journal notes are sparse, sometimes guarded; the photographs arrive from the outside, observational rather than intimate. Compared to Tracks, the book she published in 1980, the writing here is looser and less resolved. I like the space that creates. The story exists between what Davidson chooses to give away and what Smolan is able to see.

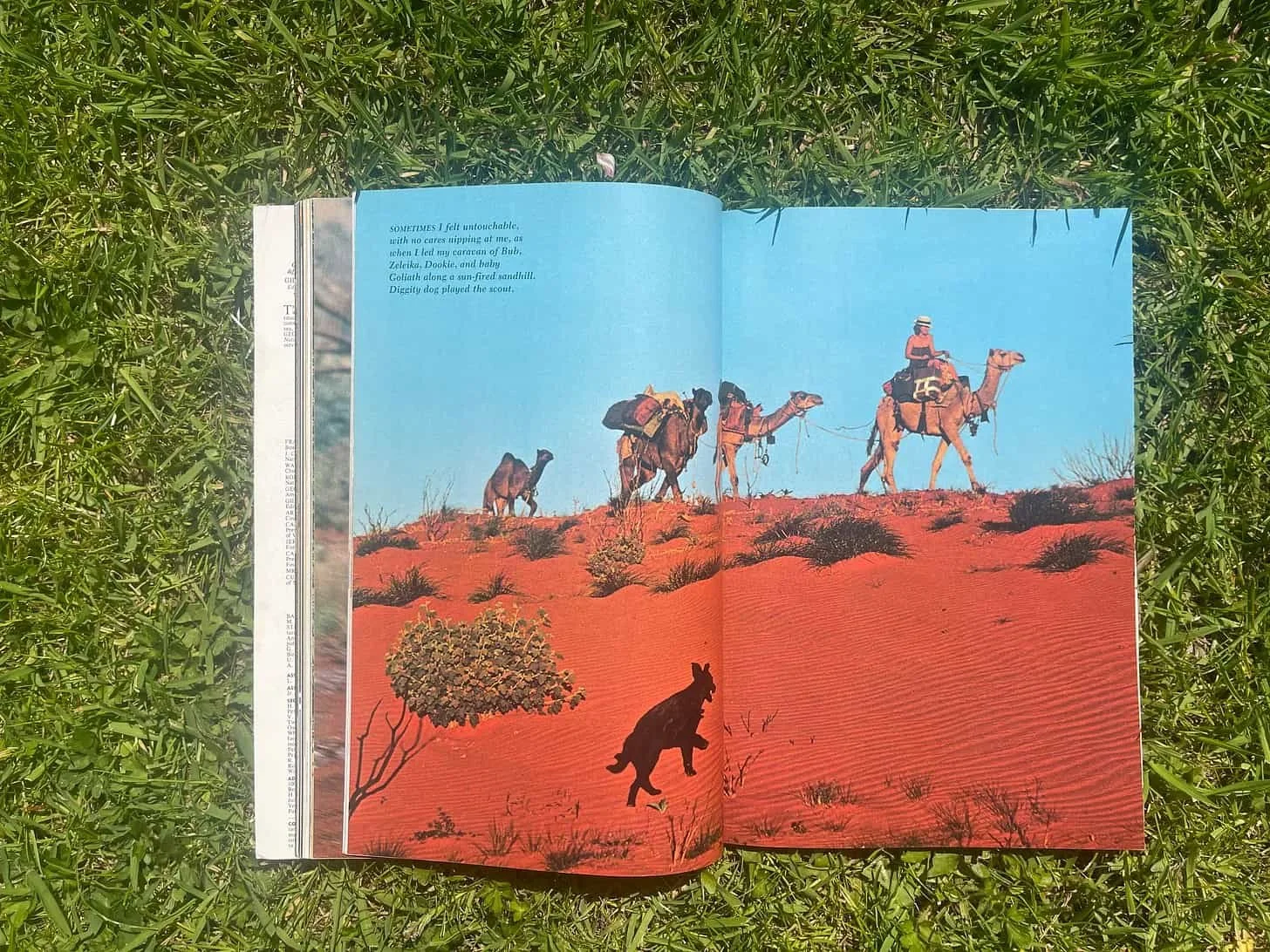

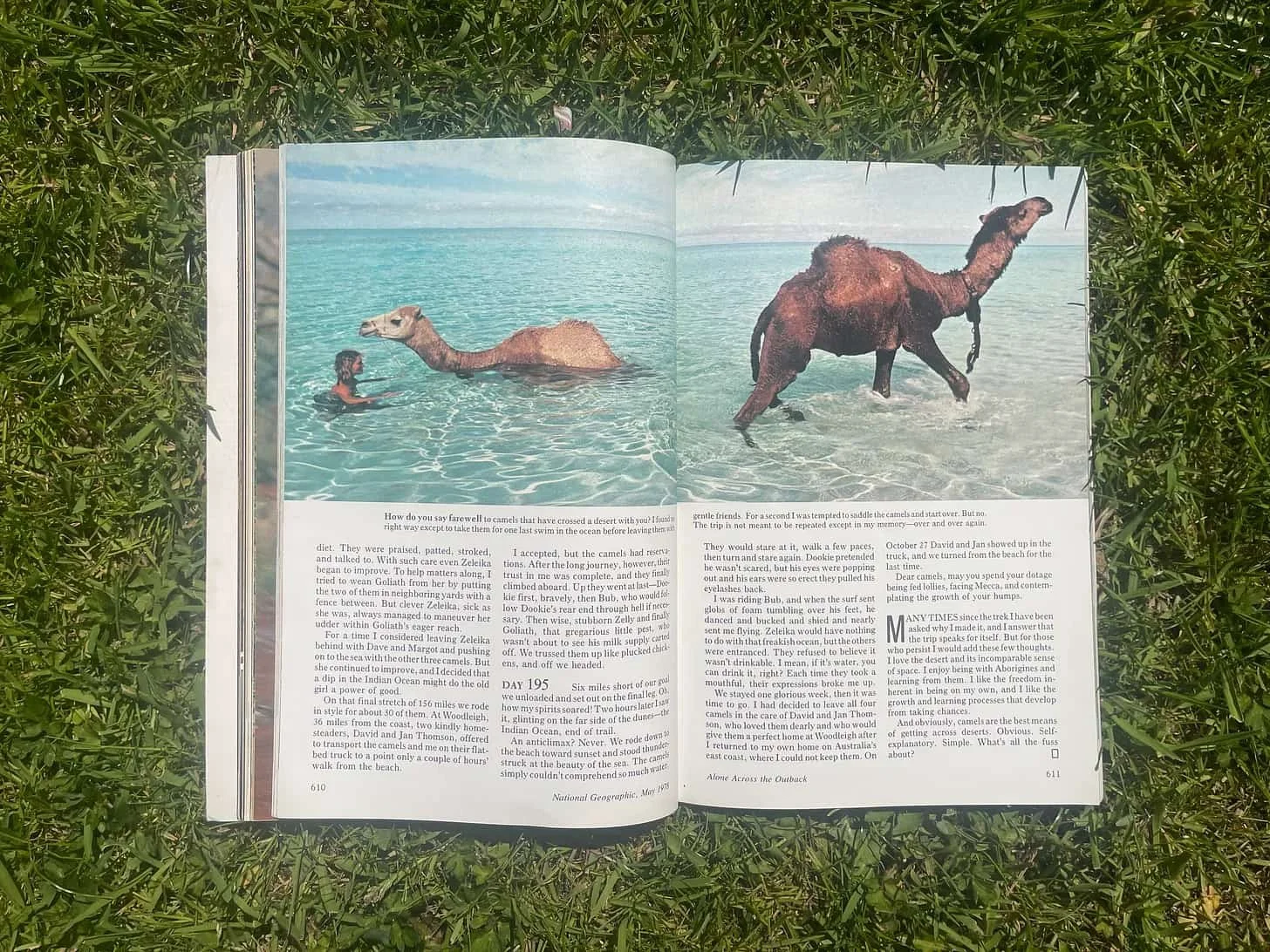

What makes the piece endure is its tenderness. Despite the friction, the photographs capture moments of warmth between Davidson, her camels, and her dog—an intimacy often missing from narratives of extreme travel.

From a photojournalistic point of view, the structure is near-perfect: the establishing frames, the long middle, through to the finale of Davidson and the camels in the ocean.

I’ve shared a few spreads below.

Even the advertisements are worth lingering over—artefacts from a slower, more confident era of travel storytelling.

National Geographic Nostalgia is a personal archive of stories that shaped how travel was seen, photographed, and imagined—revisited from a distance.