Field Guide: the Algerian Sahara

The Tassili N’Ajjer National Park: the most accessible way to visit the Sahara Desert

A Finite Window

For decades, the Algerian Sahara remained a cartographic enigma—a vast, restricted expanse of "lunar" beauty that was rarely entered. Today, thanks to a streamlined visa-on-arrival program and a shifting geopolitical landscape, Algeria has eased access to the Sahara’s most extraordinary interior.

The Tassili N’Ajjer National Park offers something increasingly rare in the modern age: a landscape of such immense scale and silence that it recalibrates one’s sense of time. This is a night sky untouched by artificial light, and a culture preserved by a generation of isolation. As the government actively encourages a return to the desert, the window for experiencing this frontier before it inevitably modernizes is finite.

The New Accessibility

Until recently, entering this landscape required navigating a labyrinthine bureaucracy that often ended in refusal. The protocols have shifted:

Entry: Algeria now provides a visa-on-arrival for travelers on organized southern tours. The previous months-long wait has been replaced by an efficient pre-approval process through local operators.

Flights: Air Algérie has prioritized the south, offering frequent connections from Paris via Algiers into Djanet, the gateway town perched at the edge of the plateau.

Topography of the Sublime

The Tassili N'Ajjer is Africa's largest national park and a UNESCO World Heritage site, inscribed for both its geological formations and its concentration of prehistoric rock art. The plateau rises abruptly from the sand seas, its sandstone eroded into formations that shift from recognizable to impossible: arches that shouldn't stand, spires too thin to be real, entire stone forests where wind has carved the rock into abstract sculpture.

The park sits in Algeria's deep south, 2,000 kilometers from Algiers and closer to Niger than to the Mediterranean. The landscape is essentially Martian—not as metaphor but as geological analog. NASA uses satellite imagery of the region to study aeolian processes on Mars. The color palette is limited: the pink-red of iron oxide, the beige of sandstone, the occasional shock of green where water collects in canyon gueltas.

The Extension: For those with a wider window, the Ahaggar National Park (accessible via a 45-minute flight from Djanet to Tamanrasset) offers a starkly different topography: a jagged, volcanic mountain range that provides a dramatic counterpoint to the Tassili’s sandstone forests.

The World’s ‘Greatest Museum of Prehistoric Art’

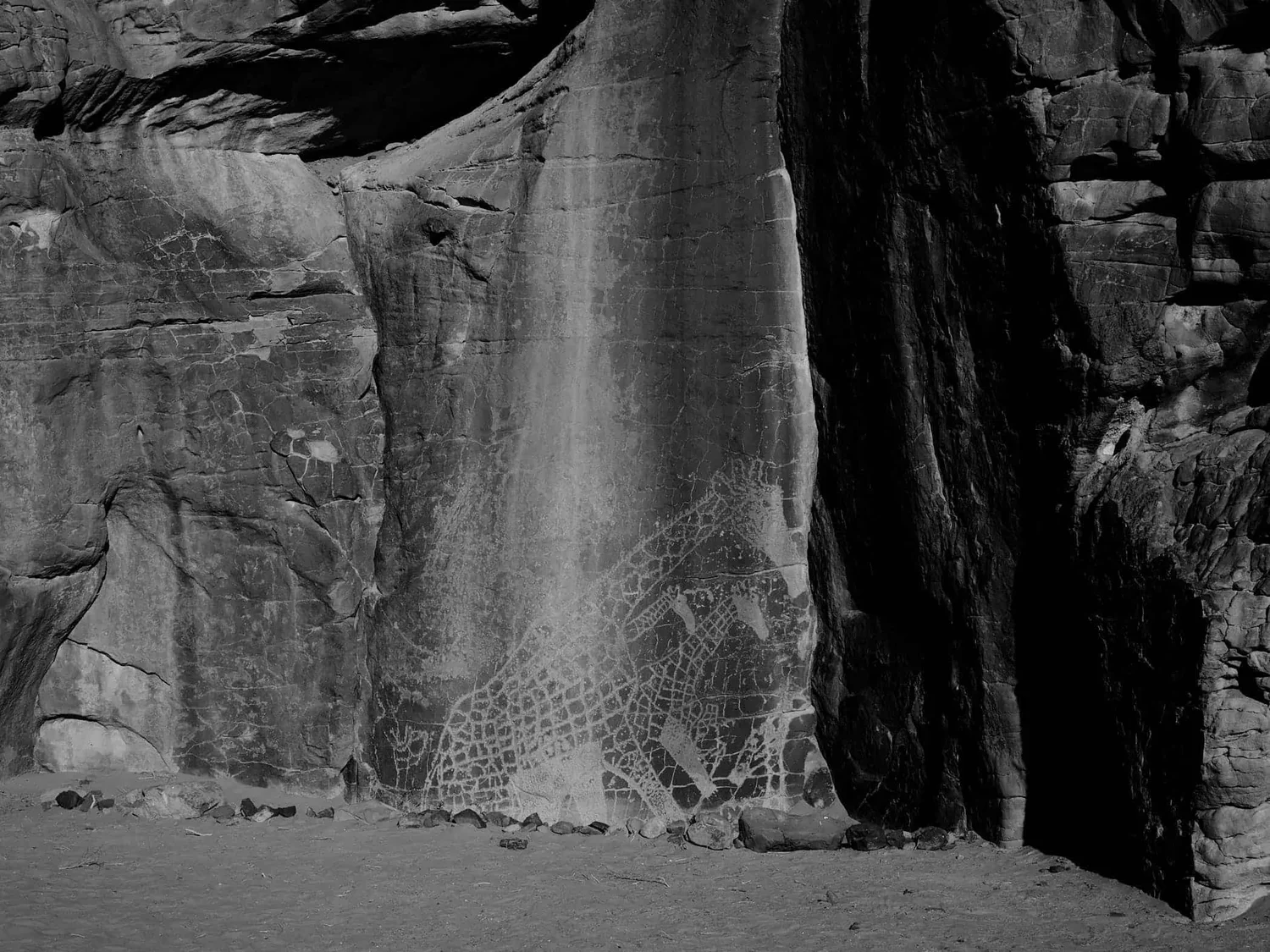

The Tassili holds more than 15,000 examples of rock art, spanning roughly 10,000 years of human habitation. The earliest engravings date to the end of the last ice age, when the Sahara was grassland and supported populations of elephants, giraffes, and cattle. The images track the progressive desiccation of the region: from depictions of abundant wildlife and pastoral scenes to the appearance of horses, then camels, then finally the abandonment of the plateau altogether.

The art is not behind glass. You walk to it across the plateau, sometimes scrambling up boulder fields, and there it is: a life-sized engraving of a giraffe, or a scene of cattle herding rendered in ochre pigment that has survived eight millennia.

The most haunting are the "Crying Cows" near Djanet—cattle with what appear to be tears streaming from their eyes, interpreted as a herder's witness to his animals dying as the Sahara dried into desert.

The Exclusivity: To understand the scale of the Tassili’s isolation, consider its rock art. While sites like Lascaux in France are heavily restricted and see thousands of visitors daily, the Tassili’s prehistoric galleries see perhaps a few hundred annually—a luxury of access that is unheard of in the UNESCO circuit.

The Tuareg Presence

The guides and support crews for Sahara expeditions are predominantly Tuareg, a Berber people whose traditional territory extends across the desert from Libya to Mali. The men wear the tagelmust—the blue or black headscarf that covers everything but the eyes—as protection against sun and sand. The indigo dye traditionally used to color these scarves bleeds onto the skin, giving rise to the description "blue men of the desert."

Tea is the lifeblood of the Tuareg. Preparation is a three-stage ritual. The first glass is strong and bitter, the second sweeter, the third heavily sweetened with mint. The process takes roughly forty minutes and serves as both hospitality and timer—a way of structuring time in a landscape without clocks. Around the campfire each evening, someone produces a guitar and the music that emerges is what Westerners have labeled "desert blues"—hypnotic, repetitive, built on cyclical chord progressions that seem designed to match the rhythm of camel walking.

The Tuareg operate on their own schedule, which is not indifference but a different relationship to time. When your guide says "we leave at dawn," this means sometime after first light, once tea has been made and gear loaded. This approach extends to payment: on my own trip, the final accounting happened after we returned to Djanet, a handshake transaction based on agreed terms and trust.

Wonders of the Tassili n'Ajjer National Park

The Hedgehog

A freestanding sandstone monolith near Tamrit, eroded into a shape so distinctly spiky and organic it appears deliberate. The formation demonstrates the abrasive power of sand-laden wind at ground level, where the rock has been undercut and shaped over millennia. Scale is difficult to judge in the desert; the Hedgehog is roughly the height of a three-story building.

The Rock Gardens (Stone Forests)

Areas across the plateau where erosion has created dense concentrations of tall, thin rock spires—some reaching 20 meters high and only a meter wide at the base. Walking through these sections feels like moving through a sculpture park with no curator, where every formation is accidental and temporary. The rock is friable; you can crumble pieces between your fingers. These formations are being slowly dismantled by the same forces that created them

Tin Merzouga: The Red Dunes

The red dunes of the Tadrart Rouge, where iron oxide concentration gives the sand an almost vermillion color in direct sun. The dunes here are among the highest in the Sahara, some reaching 200 meters. Climbing them is physically exhausting—each step up sends you sliding half a step back—but the view from the crest at sunset, when the light turns the sand sea copper, is worth the effort.

Essendilène Canyon

A narrow gorge cutting through the plateau, its walls creating shade and capturing enough moisture to support plant life—tamarisk, acacias, wild olive. The canyon floor holds a series of gueltas, natural pools fed by underground water. These pools sustain the canyon's small population of Barbary sheep and various bird species. The water is clear and cold, a strange luxury in a landscape where ambient temperature regularly exceeds 40°C.

The Crying Cows (Aghram)

Neolithic engravings south of Djanet, depicting cattle with what appear to be tears on their faces. The prevailing interpretation is that these mark the transition from the African Humid Period to the Holocene's arid phase—the moment when the Sahara became desert. Whether this reading is accurate or romantic projection is debatable, but the images remain affecting: evidence of human witness to catastrophic environmental change, preserved in stone.

Practical Considerations

Season: November through March. Summer temperatures make the desert lethal; no reputable operator will take clients during those months.

Duration: Seven to ten days for Tassili N'Ajjer. Longer trips can incorporate the Ahaggar National Park to the west, accessible via a 45-minute flight from Djanet to Tamanrasset.

Access: International flights land in Algiers. Domestic flights continue to Djanet (approximately 2 hours). This routing adds time but the alternative—overland from Algiers—takes multiple days and is not recommended.

Visas: The visa-on-arrival program functions, but requires advance coordination with your tour operator. Processing through an Algerian consulate remains possible but unpredictable, with approvals sometimes arriving days before departure.

Currency: The Algerian dinar is not available outside Algeria. Bring euros to exchange upon arrival. Credit cards are essentially unusable in the south. Cash economy only.

Communication: Mobile coverage is intermittent. Purchase a local SIM at Algiers airport or arrange an eSIM before departure (I use Saily). Some hotels in Djanet offer WiFi, but connection quality varies.

Cost structure: Expect £1,000-1,500 for a week-long tour with a local Tuareg operator, covering transport, food, and camping equipment. International operators charge significantly more (£3,000-5,000) but provide English-speaking coordination and additional insurance coverage.

Guides: The Sahara is not navigable without local expertise. GPS is insufficient; landmarks shift, tracks disappear, and water sources are known only through experience. Travel requires a guide, support crew, and backup vehicle. This is non-negotiable.

What to bring: Wide-brimmed hat, good sunglasses, high-SPF sunscreen, walking boots suitable for rock scrambling, water bottle, headlamp. The Tuareg appreciate small gifts—chocolate is traditional.

Operators

Direct experience: Tito Khellaoui (Instagram: @titokhellaoui, French-speaking) and Pióra Klinger (Instagram: @algerian_sahara_lover, English support for non-profit trips).

Established Algerian operators: Tinariwen Tours and Duneya Tours (Tuareg-owned, no direct experience).

International options: Wild Frontiers (UK-based) and Native Eye Travel (UK-based), both offering packaged Algeria tours.

Independent research: Chris Scott's Sahara Overland website remains the most comprehensive resource for desert travel logistics.

Standard disclaimer: Verify current travel advisories through your government's foreign office. Security situations evolve. This information is current as of December 2025.

RELATED POSTS