Silence and Sagebrush

Alone in a Cabin in the Nevada Desert

After five days at the cabin, I cycle to a hill that gets one bar of mobile signal and pick up an email from Phil, my emergency contact in Wells:

“Nick, if you see this, leave the car bonnet raised, facing north — kangaroo rats can build a nest in your engine compartment in 24 hours, and they’re adept at chewing through wires.”

Having spent the last few days among the wild community of animals around the cabin in the Nevada desert, this warning makes me laugh, then wince. As I pedal back to the cabin, I wonder if the gang of cute kangaroo rats watching me from under the shade of my hire car had, in fact, been plotting my downfall.

I am in Nevada as an artist in residence for two weeks at the Montello Foundation, which has built a cabin on a remote parcel of land in the Nevada desert. The residency is solo; this is my first time in an American desert, and clearly, I have a lot to learn.

To get to the cabin, I picked up a hire car from Salt Lake City Airport and drove under big American skies to Montello, in Elko County, Nevada.

Montello, once a supply town for the nearby ghost mining camp of Delano, has a post office, a general store, a filling station, and a cowboy bar. Outside the bar, a group of men chat over the back of a Chevrolet truck, watched by a strangely out-of-place poodle. Behind them, an American flag slumps in the window of a shuttered house.

On the tracks opposite the town, a Union Pacific steam train is being refuelled, watched by a crowd of townsfolk, and guarded by five men in tan cowboy hats with rifles. It’s my first day in Nevada, and I’ve stepped into a scene straight out of a western.

A garishly coloured statue of an Indian chief watches over me as I pick up a packet of Lay’s chips and a bag of coffee from between the display cases of hunting knives in the general store. The stone-faced man behind the counter remarks, “I don’t know how folks can afford to eat nowadays,” as he rings up $17 on the till.

I drive half a mile along the highway and turn off onto a dirt road. The cabin lies twenty miles away over the tufted hills. The drive takes a gruelling three hours along rutted tracks — getting out repeatedly to move rocks and avoid wrecking the car’s underside. By the time I arrive, I’m so wrung out that I drag a blanket onto the porch and fall asleep.

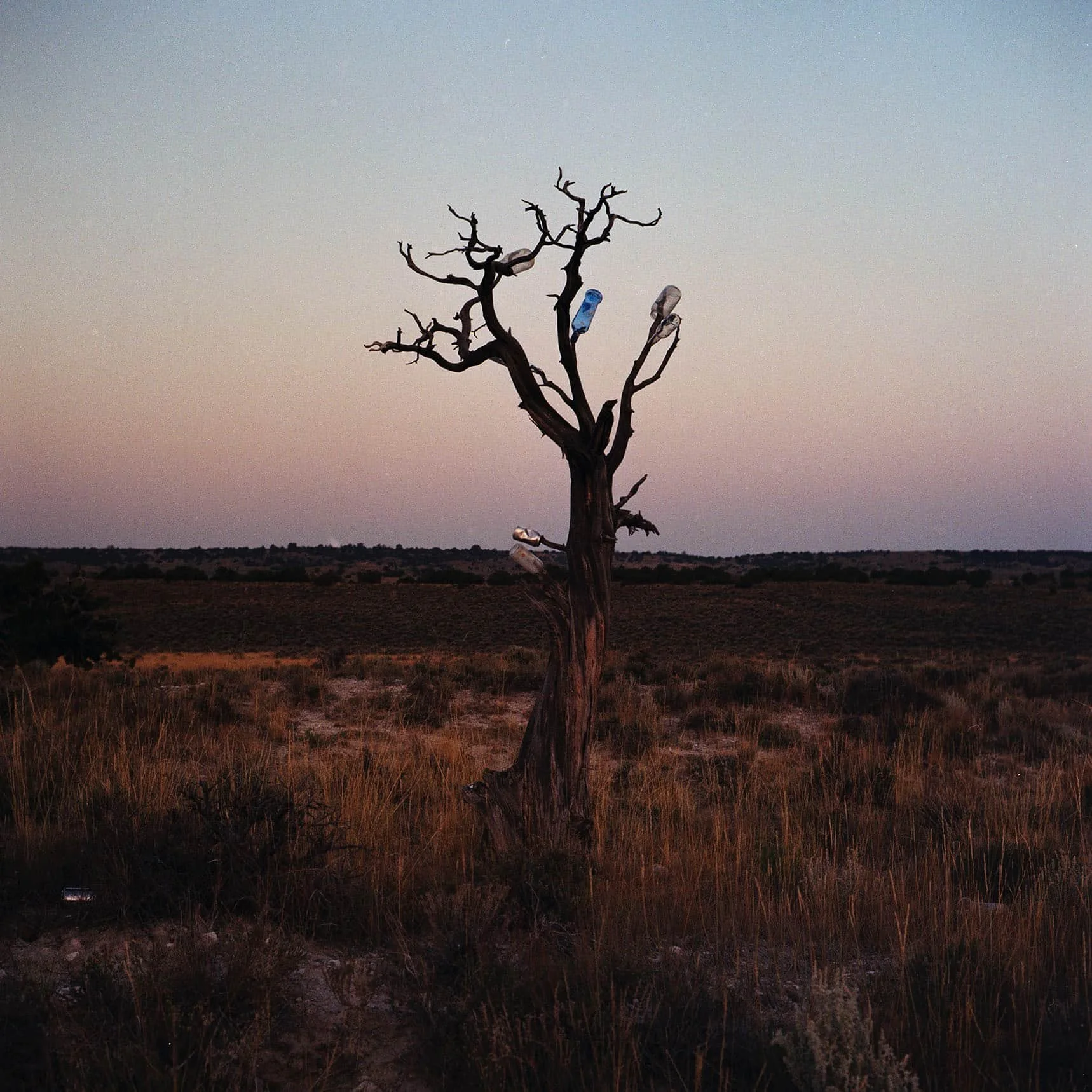

When I wake, I gaze across ancestral Shoshone land to the jagged silhouette of Nine Mile Mountain, the only landmark for miles. In front of me sits a juniper tree, a lone anchor in a sea of sagebrush. I’m in the Great Basin, where the land stretches out and time seems to slow. Barry Lopez once described this region as “one of the least eulogized of American landscapes.” There is less American myth here to get in the way of a direct experience of nature than in the country’s more iconic deserts.

The cabin is a modern design, with a double bed, a wood-burning stove, a shower, a kitchen, an emergency radio, and a verandah that runs around the building. There is a well-stocked library filled with books I’d been promising myself to read one day: Thoreau, Emerson, Annie Dillard, Rachel Carson.

While I am hardly living like a hermit, the cabin does offer a taste of embodied American solitude — a place where I can live out my Walden / Desert Solitaire dreams. I have no neighbours, no phone signal, no Wi-Fi, no TV, and no distractions.

This is a chance to experience being alone in nature, and to escape the confusion of modern culture for a while. I want, as Henry David Thoreau says in Walden, “to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach.” To be able to look at a juniper tree, an eagle, and a mouse, and to see it as its elemental self, without humanly ascribed qualities.

Mostly, I want to sit, wander, and un-think.

On my first night I walk among the juniper trees at the back of the cabin. Taking the advice of the writer Edward Abbey, I leave my head torch in my pocket and let my eyes adjust to the dimness. At first it’s unnerving, but as I continue, the night flows and I am in a world of starlight. I feel less isolated and begin to feel a part of the land I am walking through.

I hear coyotes howl under a sky thick with stars. It’s the first time I’ve heard their yowl, and I feel a stab of unease. Shoshone creation stories often portray the coyote as a trickster god who embodies chaos, cunning, and change. Returning to the cabin, I lock the doors and lie on the bed listening to animals padding around on the verandah in the night. I hear the birds on the corrugated roof above me scuttling around as a storm blows in.

It’s August, and my days are governed by the sun. I awake before sunrise and walk through the pre-dawn when the air is cool and the silence is palpable. I feel like an awkward trespasser, trying not to disturb the delicate patchwork of cacti, wildflowers, and animal burrows that quilt the desert floor. The fog from last night’s storm is scudding away before the sunrise. I sit by a juniper tree, scratch in the dirt, and unearth a half-buried Shoshone amulet.

In the afternoons I lounge on the verandah — watch the critters, doze, read, and move around the perimeter of the cabin to stay out of the sun. In the afternoon, the temperature soars, and the wind whips up out of nowhere, powerful enough to knock over my table and chair on the verandah if I don’t lay them flat.

As the days of silence mount, the desert’s emptiness seems like a mirror, reflecting my thoughts and actions back to me. In this place, the silence is sacred and there is no need to speak. A cottontail rabbit sits near me as I drink my iced coffee in the morning. I can feel my mind un-muddling.

I realise that I am alone but feel a part of everything. I know where the ground owls hunt, where cottontail rabbits live, and when the mouse who lives in the hole in the cabin wall comes out in the evening. For these animals, survival is a sacred act. For me, this is just a sojourn in nature: a chance to feel an intimacy with their world for a time.

On my final morning, the car starts without issue, and I thank the desert spirits that the kangaroo rats have spared the wiring.

On the drive back to civilisation, I stop to move a rock from the track; an eagle swoops so close that I feel the rush of air from its wings. I am hit by a wave of emotion. With my head clear after weeks away from the influence of news, social media, and people, I respond to this encounter without a self-conscious screen — a mark of my experience in the Nevada wilderness, in the silence that underpins everything.