Cape Wrath: After the Day–Trippers have Gone

STAYING AT CAPE WRATH LIGHTHOUSE: mainland Britain’s most northerly point

58°37'29.0"N 4°59'59.0"W (opens Google Maps)

It’s 3.10am and the yellow blind on the bunkhouse window glows with the light of 204,000 candles. I step out through the jumble of old boat engines into the compound. Three deer, caught in the sweep of the lighthouse beam, freeze as if I’ve stumbled into their secret gathering. At Cape Wrath, the far northwest tip of mainland Britain, I’ve walked into a Gary Larson cartoon.

As a child, I would trace my finger across Cape Wrath on the map and wonder what such a wildly named place might look like. While I imagined Old Testament fury, the truth is calmer, and stranger: “wrath” is derived from the Old Norse hvarf, meaning “turning point.” Cape Wrath is the point where the Atlantic and the Pentland Firth meet and where the Vikings would turn their longboats south toward the gentler waters of the Hebrides.

The famous lighthouse, built in 1828 by Robert Stevenson, grandfather of Robert Louis, is now automated and sits atop the 900-foot Clò Mór cliffs, which are home to huge colonies of guillemots, razorbills, puffins, kittiwakes, and fulmars. Sea stacks, arches, and remote beaches stretch along the coast in each direction. Beyond the land, an infinite sea and sky, cinematic and ever-changing.

It’s past peak tourist season, and I have the bunkhouse at the lighthouse to myself. Angie, who runs the Ozone Café, serves my evening meals accompanied by a solitary red candle, flickering wildly as Atlantic winds knife through the wooden window frame. When I describe my surreal encounter with the deer, she says in a matter-of-fact Gaelic lilt: "The red deer come to graze at night. We also look after the badgers and foxes”.

Angie lives with her father, John Ure, at the old signal station, year-round, at Cape Wrath. They keep the café open through the summer and restore the storm-battered buildings during the winter. She tells me that “storms can bring ferocious winds that can peel back a roof and demolish walls. In winter, when the cafe closes, I watch minke whales and dolphins in the Atlantic."

Twenty-seven years ago, John moved here from Glasgow with his wife, Kay. Who once made the headlines after a trip to collect their Christmas turkey went wrong—snow blocked the roads, and she was unable to return to the lighthouse for five weeks. Kay has since passed away, but John still makes the full-day trip each week to get supplies.

Cape Wrath was once home to thirty crofters, mostly shepherds and their families, but the land has always been resistant to human settlement.

Now, Angie and John are the sole inhabitants of 100 square miles of a landscape so forbidding it was left blank on the first map of Scotland. According to legend, the 16th-century cartographer Timothy Pont was too afraid to set foot on Cape Wrath, unnerved by the vast numbers of wolves. Marking the map only as “extreem wilderness” and “a place of woolfs,” before retreating south.

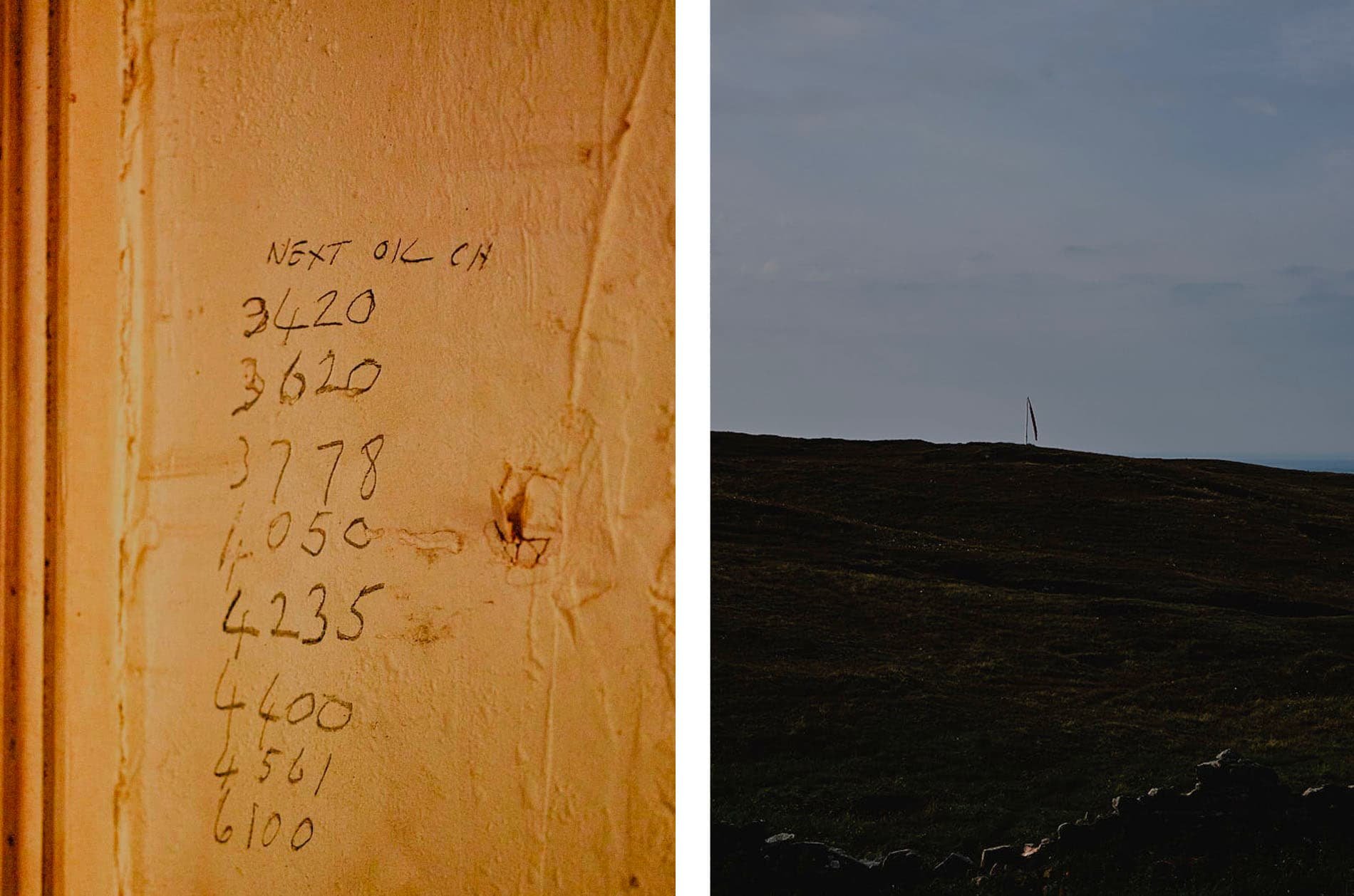

Five hundred years later, the wolves are gone, but danger persists—Cape Wrath now serves as a Ministry of Defence live firing range. John tells me that "We have to close the cafe for a couple of weeks a year when they bomb the area."

The red warning flag is down today, and the ancient minibus delivers visitors safely to Cape Wrath. They scatter across the headland, some peering over the giddying 900ft drop of the Clò Mór cliffs, while others gaze out to sea in contemplation or take selfies beside the giant foghorn. In a mixture of awe and unease, their voices carry on the northwesterly wind, remarking on its ferocity, the absence of safety fences, and the remote beauty of the place.

Inside the Ozone café, Angie fields an array of questions: "How do you cope with the loneliness?" and "Where are the shipwrecks?". But the most common request is always "Where is the toilet?", for which her answer is always "Go behind a wall." With only 50 minutes before the minibus leaves, there's barely enough time to buy a Cape Wrath stamped postcard before the visitors are once again swallowed by the single-track road, disappearing as suddenly as they arrived.

Cape Wrath is a place where thousands of people come to visit, but few linger. People come for the dramatic views over the Atlantic, but perhaps also for a peek at this stoic tower of civilization, for a chance to connect with a time when the sea was a terrifying and unknown entity. Lighthouses have a whiff of old-world romance about them and are settings for folkloric tales of human ingenuity, solitude, and resilience against the raw power of nature.

While the job of lighthouse keeper no longer exists (British lighthouses are now automated), John and Angie can stand in for us: we want to know their stories, the storms they have weathered, and the ships that have tooted their thanks in the night as they sailed safely past. "I meant nothing by the lighthouse," Virginia Woolf wrote of its role in her celebrated novel To The Lighthouse, "but I trusted that people would make it the deposit for their own emotions". Woolf saw that the lighthouse is both a symbol of solitude and of our common humanity.

Those who can brave the minor discomforts of a stay at the lighthouse can get a glimpse into the wonders of a remote headland that is closer to the Arctic than the south of England. I climb through a gap in a stone wall—the size and shape of a whale’s breech—and watch the distant drama of a freighter battling through a storm on the horizon. The lighthouse light flickers to life, its beam sweeping across the ocean and illuminating me for a moment in the majestic bleakness.

There is an older Gaelic name for this wild moorland: Am Parbh, ræθ, that stretches back to a time when maps were not drawn using grids but with stories. Which seems fitting, as grids suggest a human authority that does not exist here.

In the intermittent darkness, amid bleached animal bones and thick purple moor grass, I hear the beat of a Fulmar’s wing as it glides past my eye level. At this moment, Cape Wrath is still a blank on the map, with gifts and stories to bestow on those who pass through it. It wouldn't surprise me in the least to hear a distant howl.

Getting to Cape Wrath

Getting to Cape Wrath by any means is an adventure.

Take the combined ferry crossing and minibus service from Keoldale. The ferry crossing takes just 5 minutes, the minibus waits for you on the far shore to take you along the 11-mile single-track road to Cape Wrath.

The road passes through wild and remote moorland that is used by the British Military as a training ground.

For schedules and bookings, consult the Cape Wrath Visitor website. I just turned up and there was space. But in summer it’s advisable to book in advance.

The Journey can be done as a day trip or you can stay overnight as I did.

Stay & Eat

The facilities at the lighthouse are basic, but enough to support a few nights stay.

The bunkhouse is warm and comfortable enough. You can pitch a tent in the field just by the lighthouse for a modest fee. I camped for one night then stayed in the bunkhouse as it was very windy and I had a very lightweight tent.

Most visitors only come for the day. When I stayed in September, I had the place to myself.

The Ozone Café is open year-round, offering simple meals with vegetarian and vegan options, snacks and drinks.

Further Information

For practical details, timetables, and bookings, visit visitcapewrath.com

RELATED POSTS