Ghosts of a Green Sahara

Deep in the Algerian Sahara, ancient hands carved images of a world that no longer exists: rivers, herds of elephants, giraffes, hunters and cattle.

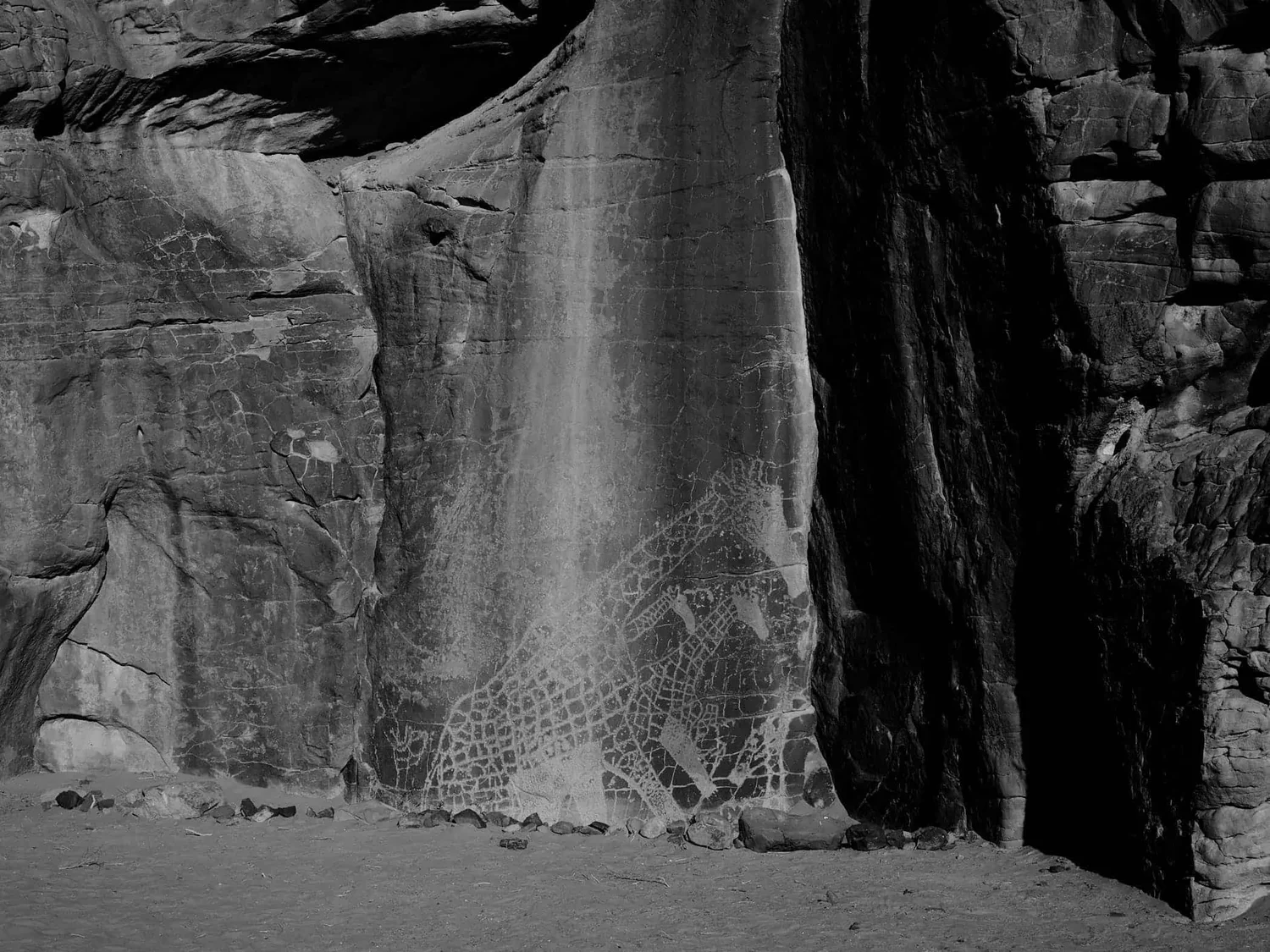

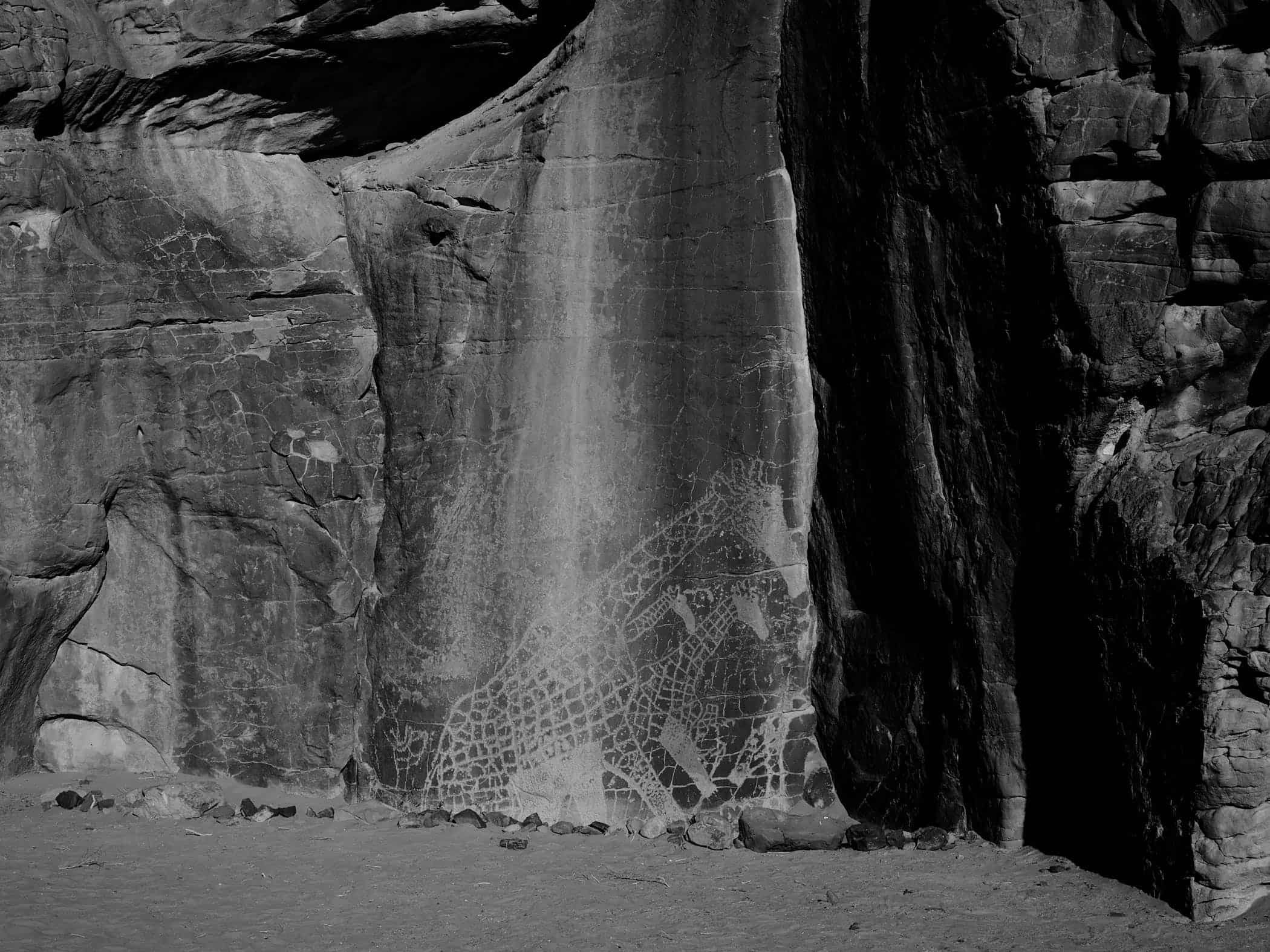

The giraffe appears without warning. I round a corner of rock and there it is: elegant neck, spotted hide, carved into stone the color of dried blood.

For a moment, the Green Sahara rises up, offering a visceral glimpse into deep time—a world of lush grasslands where sand now accumulates, and water where stone now bakes under an unrelenting sun.

The lines are confident and economical. Someone stood here—how many thousands of years ago?—and knew this animal well enough to render it in a few decisive marks. Since then, the sand has risen, burying the lower half of the body. In another century, it may disappear entirely.

Tassili n’Ajjer—the name translates as “plateau of rivers.”

Standing in a place where nothing flows, where water exists only in rigid yearly rations, the designation feels like a mistake. Until you look at the walls. Hippos. Crocodiles. Elephants drinking at pools that no longer exist. The Sahara, once, was not a desert; it was a sanctuary of permanent water and hunter gatherer civilisations that flourished before they were forced to flee.

Further into the plateau, cattle stretch across a rock face in red ochre. These are not generic animals—they have individual markings, piebald patterns, and the particular curve of specific horns. Someone loved these herds enough to record them permanently; someone wanted to be remembered as their keeper. The pigment, made from crushed stone mixed with animal blood, has lasted five thousand years.

Deeper still, on a vast slab of sandstone, the "Round Head" figures loom. Three meters tall, these human forms are topped with featureless circular heads, their bodies floating as if underwater. In the 195os, Henri Lhote, French archaeologist called one "the great Martian god," but standing in front of them now—with silence pressing in from all sides—interpretation feels insufficient. They simply are: inscrutable, and deeply human.

The progression of imagery traces the climatic shift. The oldest engravings show the extinct giant buffalo and rhinoceros—species that required ecosystems we can barely reconstruct. Then come the painted cattle, marking the dawn of pastoralism. Then horses pulling chariots at full gallop. Then the ‘crying cattle’ near what is thought to be a dried up watering hole near Djanet. Finally, the camels—the ultimate concession to aridity, to a world where water became a memory and movement became survival.

More than fifteen thousand images have been catalogued across this sandstone labyrinth of the Tassili n'Ajjer. To see them one requires a Tuareg Guide who have known these routes for generations. There are no roads here, no infrastructure. The same remoteness that has protected these images for ten millennia now requires effort to witness.

The plateau continues to erode. Wind, sand and rare rain wear the carvings down, though slowly. But for now they endure—giraffes, elephants, and hippos in rivers that no longer flow. They are evidence that the Sahara was once something else entirely, and a reminder that what seems permanent is always, on a sufficient timeline, provisional.

RELATED POSTS