The Tuareg: A People Without Borders

Nomadic instincts run deeper than walls

“Tuareg culture is written in people, not books,” says my guide Tito, as I leaf through a flimsy pamphlet at the Museum of Tuareg Culture in Djanet, Algeria.

Nearby, a sign on a wobbly stand proclaims, “Intangible cultural heritage lives only within and among people.”

I begin to wonder why bother with the museum?

Whilst lovers of antique tents, picked fish and small asteroid fragments might pass a pleasant 10 minutes here, the true riches of the Tuareg lie outside the walls.

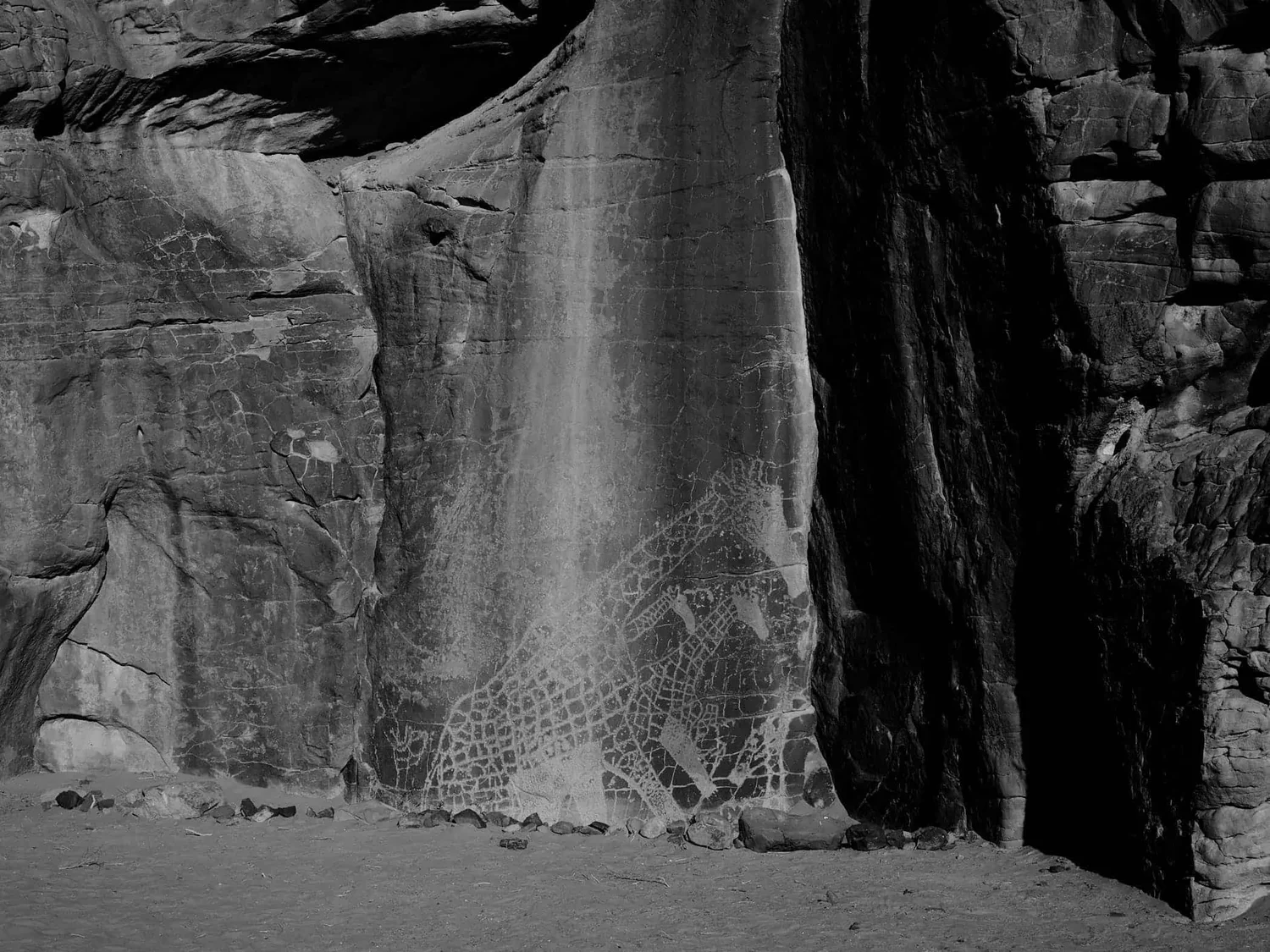

To the Tuareg, the Sahara Desert is a vast repository of signs, history, art, and texts written into stone and sand–an intimate ancestral geography spread over a desert landscape of thousands of miles.

At each camping place: a memory.

At each grave: a story.

At each oddly shaped rock: a myth.

Signs written in Tomachek (the Tuareg language) on sandblasted rock tell where water can be found, and who has passed this way.

Tito tells me that the Tuareg are “the original nomadic wanderers of the Sahara”, and “do not recognise borders”.

When Algeria gained independence in 1962, it secured its frontiers and ended the Tuareg’s cross–border wanderings.

Tito’s family are now scattered across Algeria, Libya, and Niger.

Later, Tito takes me to his house. From the hallway, I hear the refrains of the desert blues: an acoustic guitar, Tende drums, and voices layering over tea and conversation.

Two Tuareg musicians—members of Tito's extended family—are sat on traditional rugs on the floor, instruments resting easy in their hands.

The house is built around one large living room with high ceilings and small light bricks high up the walls in lieu of windows.

While he makes the tea, Tito explains that to the Tuareg, the Sahara is a vast ancestral geography spread across thousands of miles.

At each camping place: a memory.

At each grave: a story.

At each oddly shaped rock: a myth.

Signs carved in Tamashek (the Tuareg language) on sandblasted rock tell where water can be found, and who has passed this way before.

Tito tells me that “My grandfather was a nomad and built this house when he settled.”

I look around. There is a fitted kitchen, but food and tea are prepared on the floor, desert-style, over open coals in a portable cast-iron grate.

Apart from a small table set aside for Western visitors, there is nothing here that would look out of place in a nomad’s tent.

There is none of the ‘Kipple’— clutter or useless junk— of consumerism here.

The walls of this house do not break nomadic life. The same rituals persist here—gathering, music, tea, fire—as they do in the desert.

As Bruce Chatwin wrote “If this were so; if the desert were ‘home’; if our instincts were forged in the desert; to survive the rigours of the desert…then it is why possessions exhaust us.”

With thanks to Piora Klinger and Tito Khellaoui.

Text excerpt from The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin.

RELATED POSTS