Reading the Sahara

Five books trace how the Sahara has been written: first as void, then as revelation. Only one was written by someone who belongs to it.

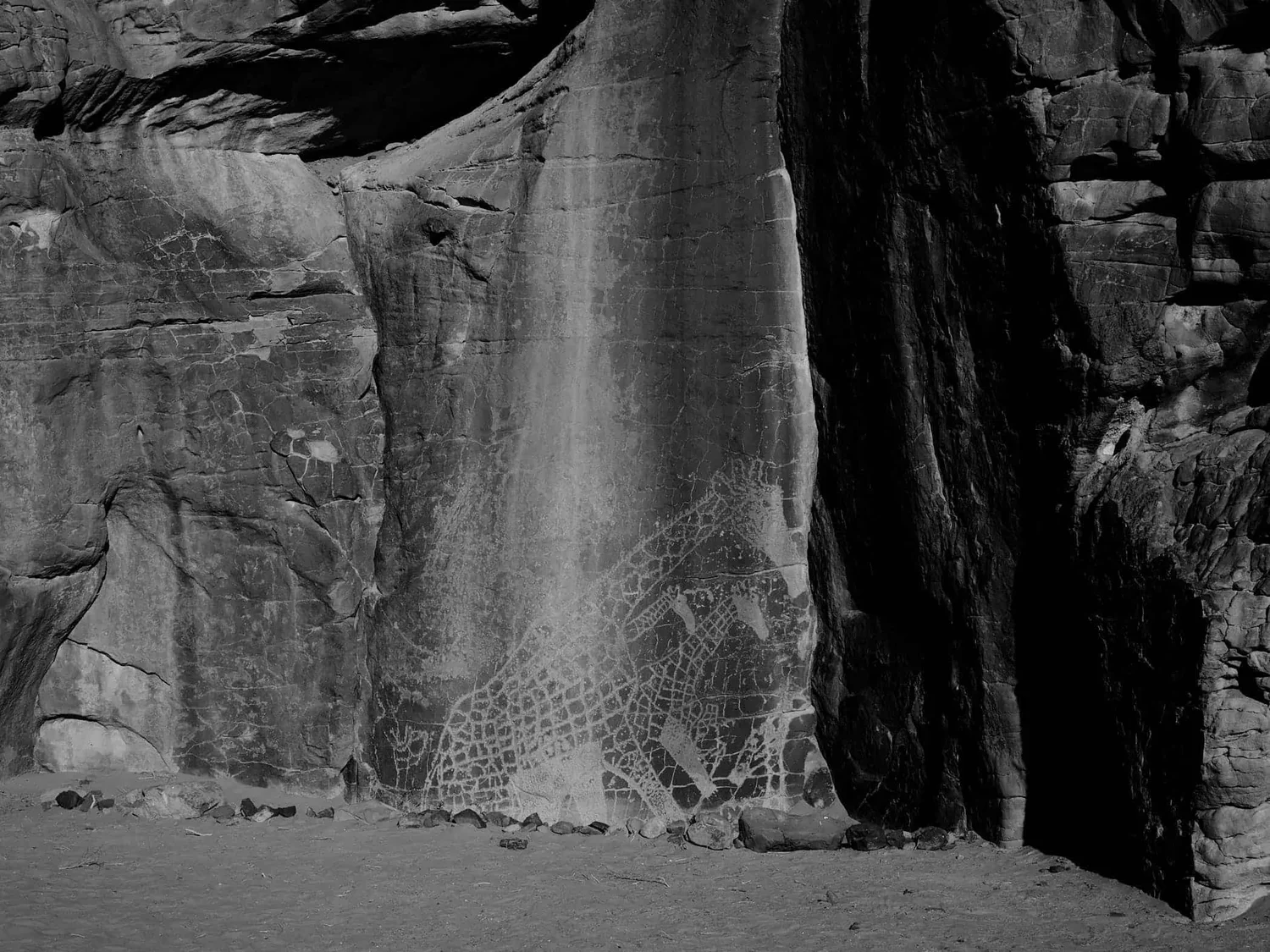

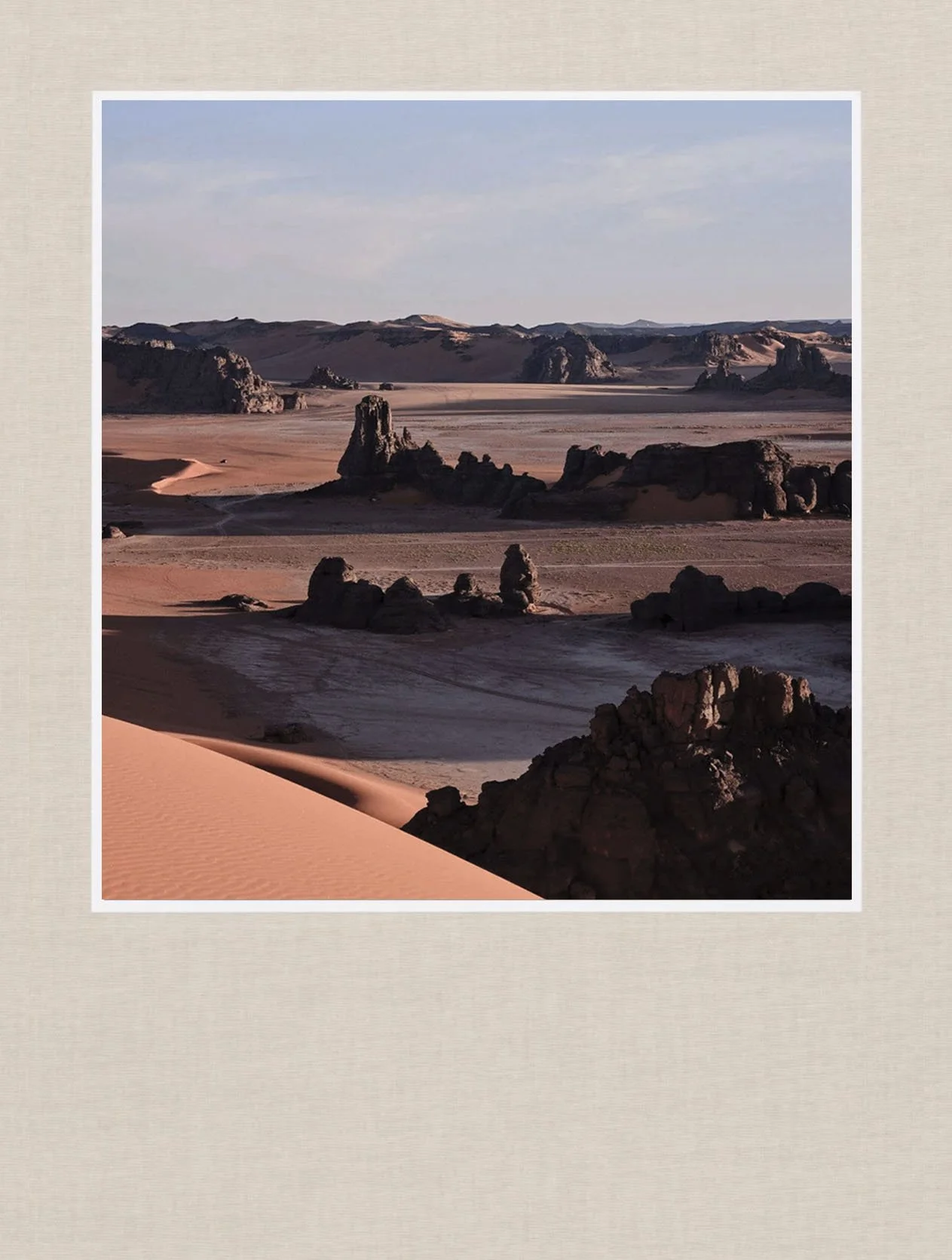

The Sahara has rarely been written about as a destination, but has often been described as a void. A blank on the map. A hostile absence separating what mattered from what did not. This idea traveled easily: it justified the lines drawn in ink, the caravans of stolen goods, and the assumption that nothing worth knowing existed there before the first explorer arrived. Writers arrived expecting emptiness, and initially, they found what they came for: vastness, silence, disorientation. Yet the longer the Sahara is endured, the less it behaves like a vacuum and the more it reveals itself as a heavy, accumulated history.

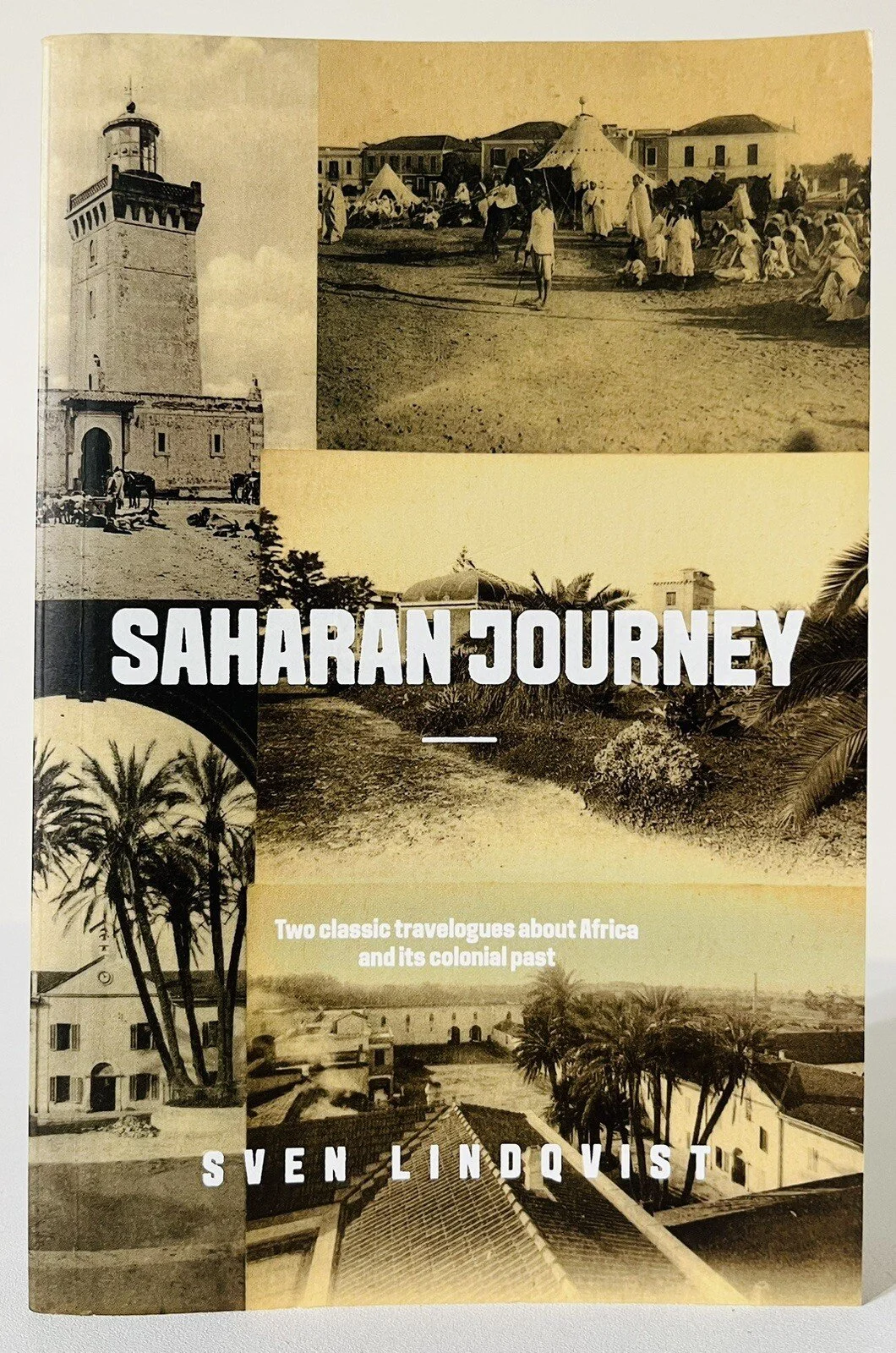

Sven Lindqvist enters the Sahara suspicious of "wonder." His journey through Algeria and Morocco is driven by unease, and Saharan Journey reflects a landscape that refuses to be a postcard. “What is missing,” he writes, “is the courage to understand what we know and draw conclusions.” His fragmented style mirrors the broken history he uncovers: the desert becomes an archive of European violence, its vastness exposing how easily cruelty hides in the heat. What appears empty is actually saturated with what has been disowned. The Sahara does not erase the past—it preserves it, stripped of ornament. What was named a "void" was, in fact, just a convenient way to look away. Lindqvist pulls at threads that lead inward, into the guilt of the visitor, showing how the idea of an "empty" space justified everything Europe chose to do there.

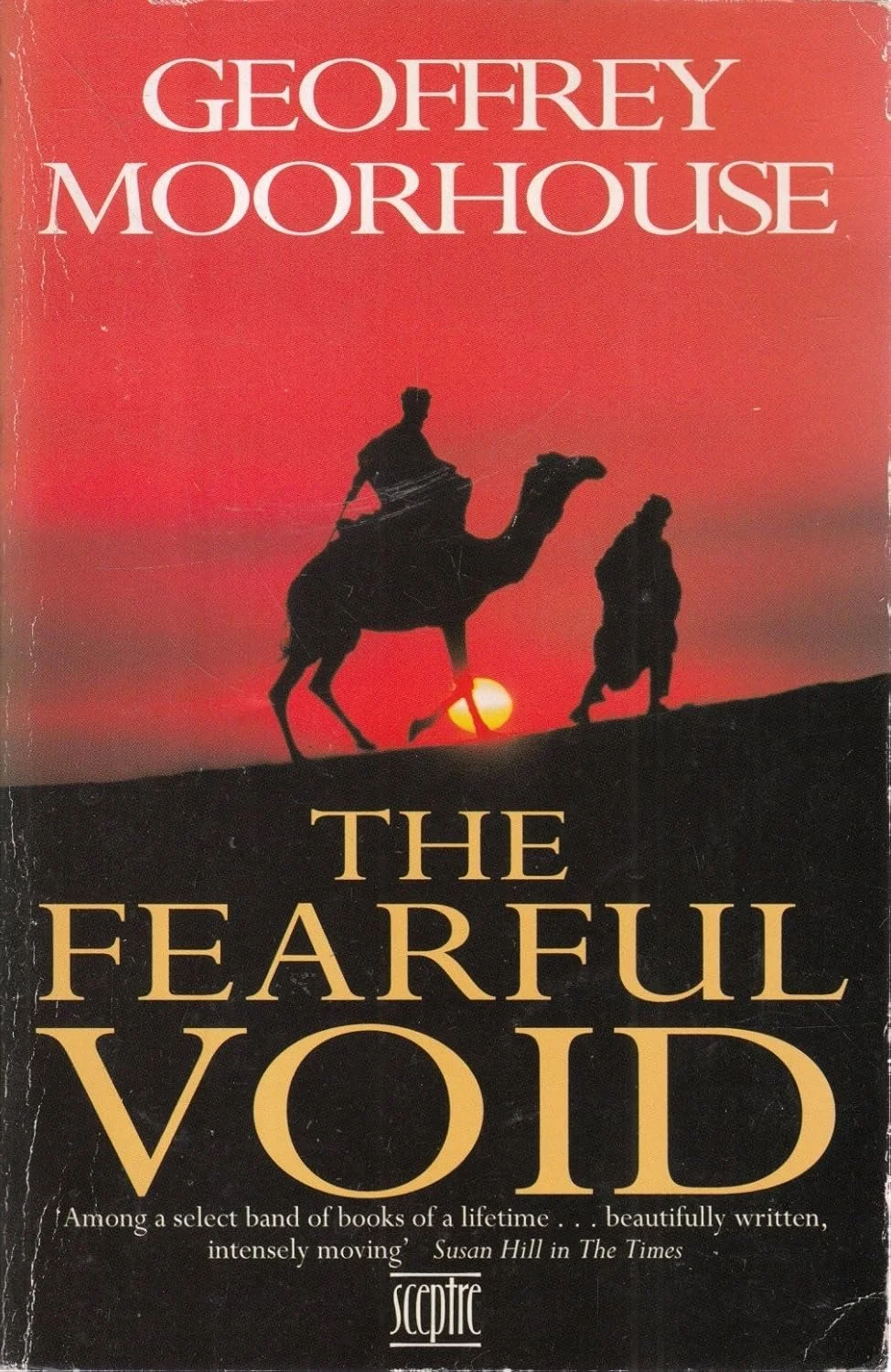

Geoffrey Moorhouse set out to cross the Sahara on foot and discovered that the distance was the least of his problems. “It was because I was afraid,” he writes, “that I had decided to attempt a crossing.” The Fearful Void chronicles his attempt to traverse 3,600 miles from the Atlantic to the Nile, but what piles up is not mileage—it is terror. The desert tests the very reason for being: why continue, what sustains a man’s spirit, how much of fear is just a ghost we bring with us. As he moves further into that “awful emptiness,” the hunger and the heat turn the journey inward. Moorhouse sought the desert as a mirror and found only his own unraveling reflected in the sand. The emptiness was his own, and the book refuses to offer a happy ending or a grand transformation. What the Sahara reveals is how easily we break—and the question of whether we can stand the sight of our own fragility.

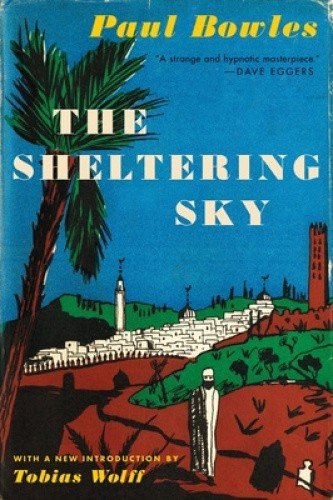

Paul Bowles understood that the desert does not destroy people—it simply strips them bare. The Sheltering Sky follows three Americans into North Africa, and what begins as a search for adventure curdles into a slow disappearance. “Because we don’t know when we will die,” one character reflects, “we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well.” The Sahara dries up that illusion with cold, surgical precision. Bowles writes with a detachment that mirrors the desert’s indifference; his characters disintegrate not through drama, but through exposure to a place that offers no mercy and no meaning they can recognize. They arrive as blank slates, and the desert leaves them blank. Bowles captures the terrifying clarity of the heat: the Sahara makes visible the cracks in the soul that were already there

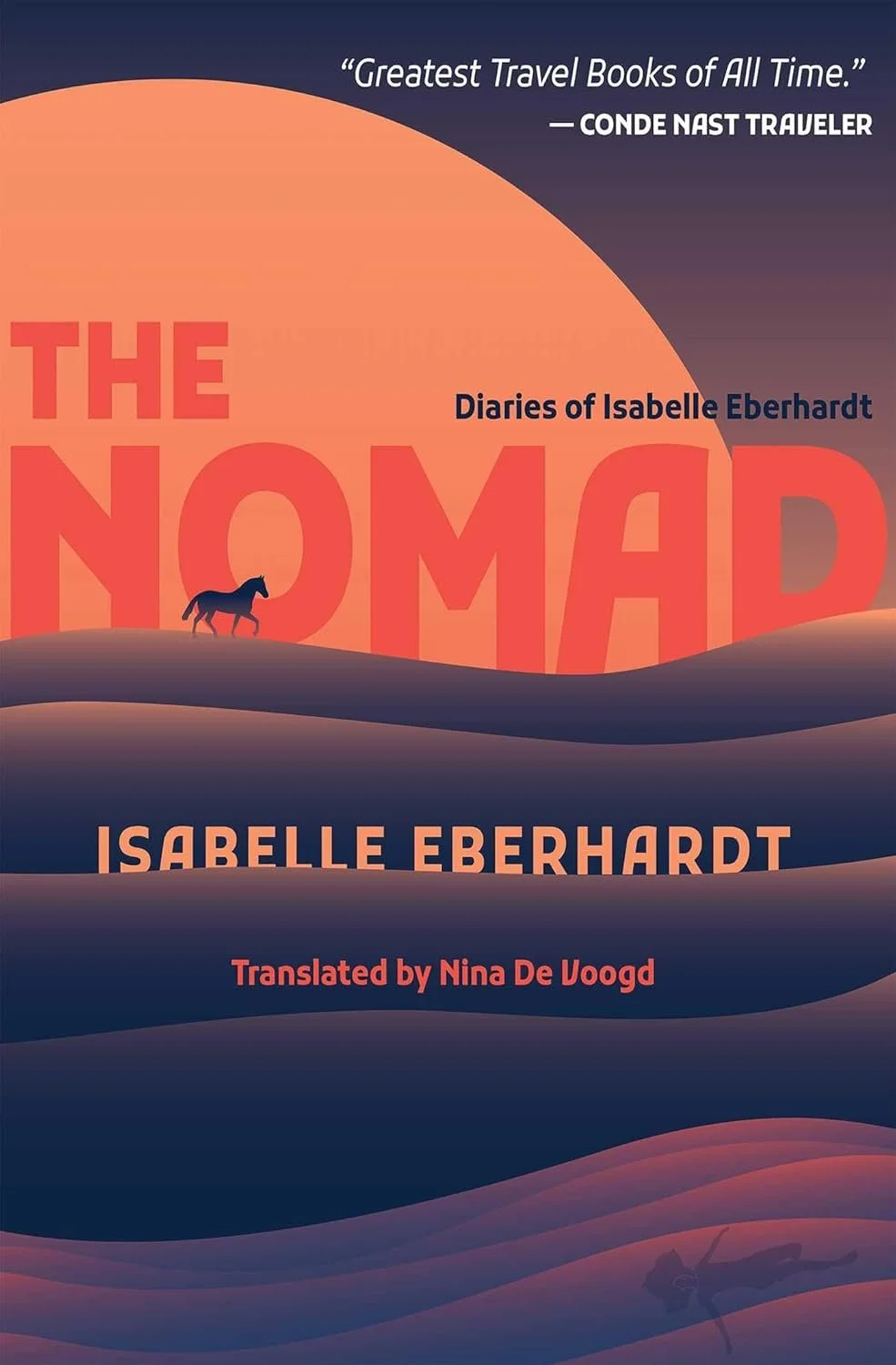

Isabelle Eberhardt lived in the Sahara as few Europeans ever dared. The Nomad, drawn from her diaries in Algeria and Tunisia, records a life deliberately cut loose from the world. She converted to Islam, dressed as a man, rode alone into the dunes, and wrote with a restless, raw intimacy. For Eberhardt, the Sahara is neither a test nor a metaphor—it is a refuge. It is a place where the rules of society dissolve and solitude becomes the very air she breathes. She does not just describe the landscape; she lives against it, moving through the sand and her own identity at the same time. Where others projected their own fears onto the desert, Eberhardt let herself be swallowed by it. Her writing carries a sense of danger, not as a tragedy to be avoided, but as the only way to truly live.

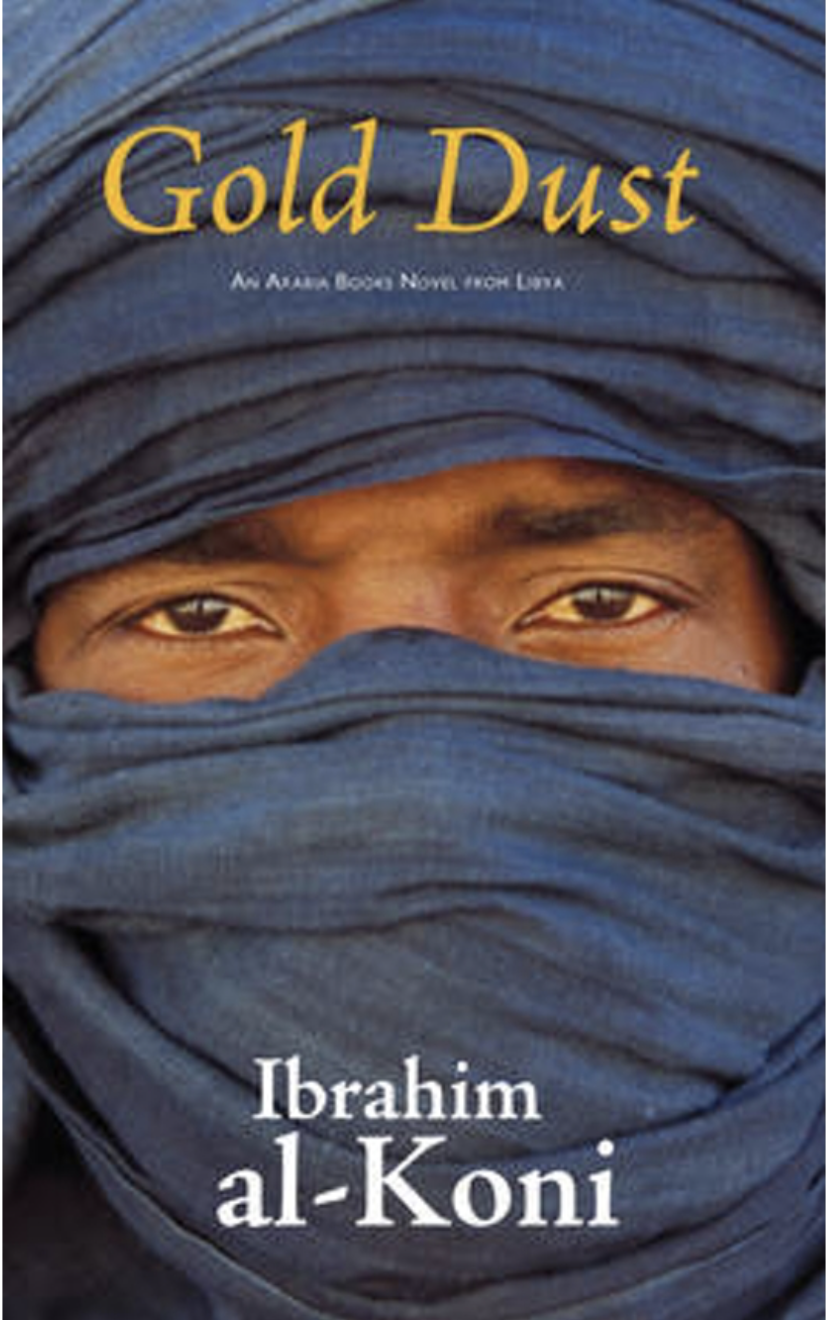

Ibrahim al-Koni’s Gold Dust dismantles the outsider's perspective entirely. Al-Koni is Tuareg, raised in the desert, and he does not write the Sahara as an ‘encounter’ but as a home. His novel follows a young nomad named Ukhayyad and his bond with a pale Mahri camel, but the story moves through layers that go deeper than any map—reaching back into myth, mysticism, and the ancient law of the sand. “The desert was a merciless place,” al-Koni writes—merciless not because it is empty, but because it is so precise. The Sahara here is crowded: with spirits, with ancient rules, and with knowledge older than the empires that tried to cross it. Where Western writers see a void, al-Koni sees a living, breathing world. It is a system of signs mistaken for silence by those who do not speak the language. The void was never the desert. It was always the visitor.

RELATED POSTS